The subsea market includes a broad swathe of offshore equipment and service providers that have primarily served the offshore oil and gas sector. It has been a very competitive arena, with high barriers to entry and requiring extensive capital outlay.

However, the energy transition continues to upturn established ways of working and reduce the demand for once profitable business lines, especially for those companies providing services to operators in Europe, where the pace of oil and gas phase out is likely to be fastest.

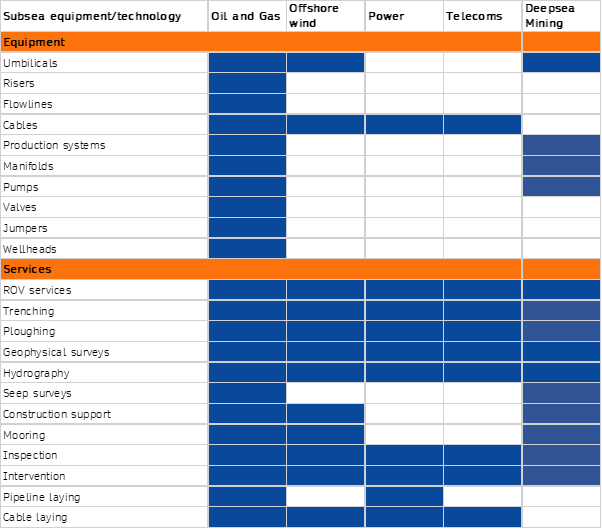

Subsea has a natural crossover in the offshore wind space, as well as other applications like telecoms and power, but those areas specific to oil and gas, such as subsea tree manufacturers, may struggle to diversify.

Investors are keenly assessing the possibility of shifting the revenue base of offshore service businesses from oil and gas to renewables as a unique value accretion opportunity. While most oil and gas related businesses will trade at sub-8xEV/EBITDA multiples, those exposed to renewables could fetch in the mid-teens.

Changing the revenue mix to be predominantly derived from renewables within a typical five-to-seven year holding period will be no easy task, despite the sector’s relentless growth.

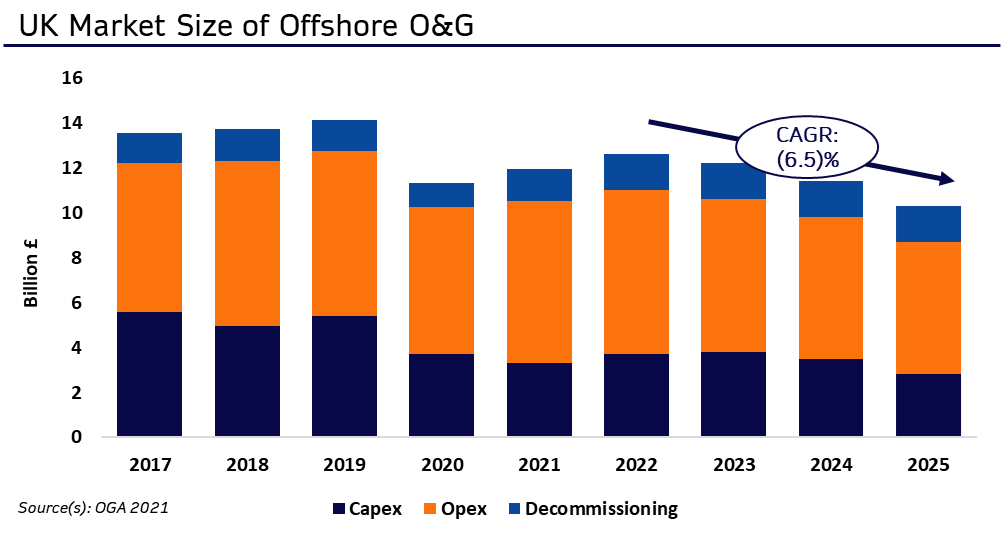

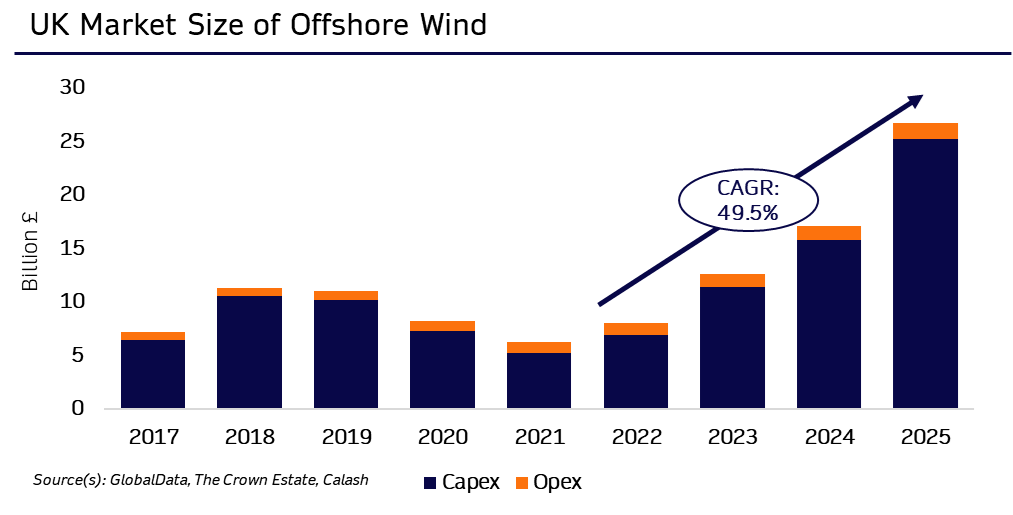

The comparative market sizes of the offshore oil and gas and offshore wind markets will naturally tip from one to the other over the coming decades, especially as we approach 2030 and the latest round of projects resulting from recent leasing rounds come to commissioning.

The offshore oil and gas market experienced a decline through 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which dramatically reduced offshore operations and partly contributed to a steep decline in the oil price.

It remains a large and strategically important market that will be relevant for several decades, especially for gas. Moreover, energy security concerns have caused a reversal of policies that had previously stymied new exploration and development spend. This volte-face has resulted in several projects being announced or sanctioned in the last few months, with six North Sea oil and gas fields now earmarked to be fast tracked by the UK government.

The tension between Russia and the West has caused a squeeze on supply, as Russian oil and gas is increasingly turned away, resulting in high commodity prices for the foreseeable future.

Capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operational expenditure (OPEX) had already been expected to show a slight increase over the next year, as above, but this is now likely to become a much longer bull market that has yet to be fully reflected in available data.

Offshore wind capital expenditure is smaller than oil and gas but is in line to outpace and grow rapidly from 2023 onwards.

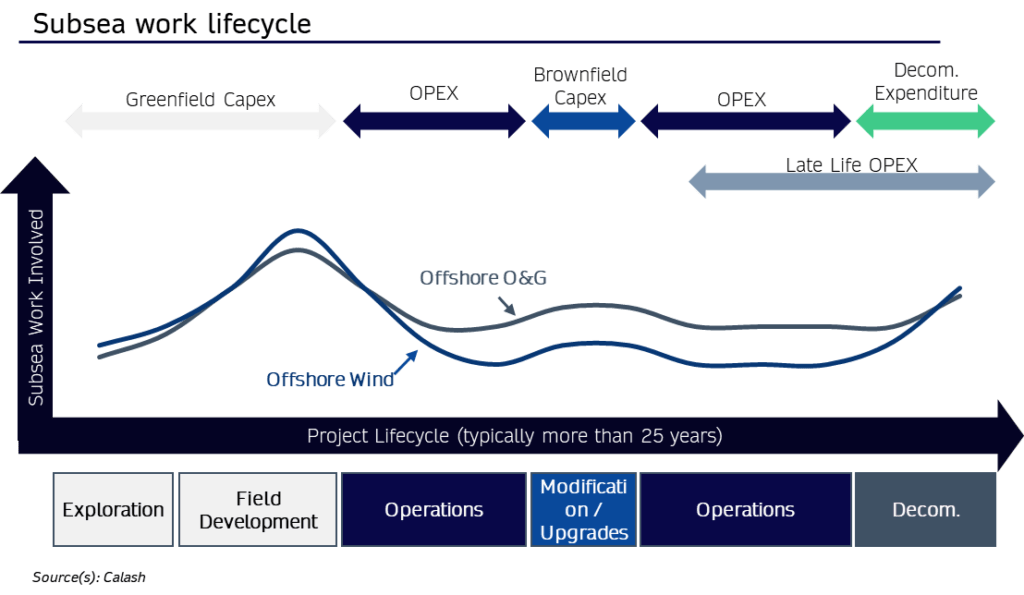

However, the relative requirement of subsea workload varies significantly between the installation and maintenance of an oil and gas rig – be it fixed-bottom, jack-up, or semi-submersible – and that of an offshore wind farm.

Marginal difference

The key issue for subsea equipment and service businesses looking to transition to a predominately offshore wind-derived revenue base is the lower profit margin to be had in the emerging segment.

While the project pipeline in offshore wind seems ever expanding, a business needs to secure a much larger contract book to maintain the same cash flow that would be generated by an equivalent amount of work in oil and gas.

The level of engineering for offshore wind is simply far less technical than hydrocarbon extraction. Subsea equipment and services will be most needed in the initial phase of offshore wind projects as part of geophysical studies and engineering, procurement and construction (EPC). The laying of umbilical, flexibles and inter-array cables is an integral part of connecting a wind farm to an offshore substation, and then on to the grid.

The role of subsea equipment in the operations and maintenance (O&M) phase of a wind asset will be significantly less than in oil and gas, given the level of seabed activity is lower.

Conversely, much of the future oil and gas spend will be focused on asset maintenance and life-extension of existing facilities and subsea infrastructure, rather than greenfield EPC.

A wholesale replacement of oil and gas revenue with offshore wind is unlikely, especially in the short term when oil and gas expenditure is expected to rise significantly.

Much of the energy transition rhetoric from offshore service businesses may quieten as the oil and gas upcycle steepens. It’s within this backdrop of higher traditional revenue streams that incumbents must decide how to reinvest to win market share in the highest margin offshore wind applications.

In parallel, new relationships need to be formed with operators, tier-one marine service providers, and emerging pure-play wind EPC and O&M firms. While the customer base may remain similar, the decision makers are likely to change.

Below the waves

There are areas of the sector that have very little application beyond oil and gas, like subsea valves, while other areas, such as subsea umbilical, risers, and flowlines (SURF) have a degree of crossover.

Investors and strategics need to target the equipment and services within the subsea space that are of most application to the CAPEX phase of wind projects, such as ROV cable work, given the higher profitability of this area.

Focusing on subsea technology developers and suppliers could be more appealing, given these businesses largely avoid lumpy, project-based revenue and, compared to engineering services, are easier to apply to new jurisdictions through leasing, joint ventures and partnerships.

Europe is the frontrunner and blueprint for offshore wind rollout in other regions, notably North America, where further contracts could be won as the project pipeline in these areas matures.

The area of floating wind, while still nascent, will also require greater use of SURF equipment and services, given the need for mooring lines and more substantial cables in deeper oceans.

Technology and services that have specific cross-over between deepwater oil and gas and floating offshore wind could represent attractive areas of investment, but would unlikely see a widescale deployment until that market matures.

The parts of the subsea infrastructure that transport fluids, such as flowlines and risers, will not have a crossover use. That is not to say that the supply and engineering of these systems will not still generate significant revenue from traditional oil and gas work, but it won’t move the needle in terms of the proportion of the business weighted to renewables.

Decision makers are minded to specifically target market share and intellectual property in the mooring, cabling, and umbilical spaces. As with oil and gas, offshore wind developers want to reduce maintenance costs and the robustness of subsea infrastructure will add to the efficiency and overall lifespan of a project. Technology and equipment that can demonstrably show a reduction in vessel time will be of high value to the offshore wind industry.

Offshore wind is not the only route for oil and gas focused SURF providers to seek diversification. The UK has several multibillion-pound carbon capture and storage projects in development, notably the government-backed East Coast Cluster and HyNet schemes, which ultimately hope to pump millions of tonnes of CO2 back under the seabed.

These projects will largely seek to piggyback off existing offshore infrastructure but will no doubt require extensive repurposing of subsea pipelines and processing systems to reverse gas flows and inject the unwanted carbon.

While opportunities in this space will be limited to the megaprojects, it does pose an attractive alternative use of SURF equipment and services for those able to win market share.

Diversification could also come from subsea telecom cable laying and electricity interconnector projects, however, while this market is likely to grow it does not provide a continuous project pipeline to replicate oil and gas.

Another adjacent, but nascent, area will be deep-sea mining, given large reserves of the minerals critical for the energy transition, such as cobalt, are to be found offshore.

Much of the heavy subsea engineering needed for oil and gas would be replicated by seabed mining, and the scope of technical crossover would be significant. Whether deep-sea mining becomes commercially viable is another question.

Realising growth

For financial investors, notably private equity, much of this continues to boil down to whether a business currently targeting oil and gas can successfully diversify its revenue base within the life of the investment.

This could occur organically, picking up offshore wind contracts from existing customers that are themselves branching out. But passively relying on the underlying macroeconomics of the energy transition will not result in a subsea equipment business growing at a rate acceptable to a private equity sponsor. Adapting an existing suite of products may prove a more cost-effective route, albeit one that brings with it added technology risk.

Incumbent subsea equipment and service providers may need to inorganically grow their offerings to successfully reposition through bolt-on acquisitions. Unfortunately, there are few credible technology targets in the space, and those that do have a high-value subsea intellectual property for use in offshore wind will attract significant M&A premiums.

A transformative alternative would be to merge with a counterpart already a champion in these adjacent markets, and to create an integrated, one-stop shop, for traditional and emerging subsea work.

There may be an inclination to do nothing. Many management teams will be looking to the next couple of years as a time of intense offshore oil and gas activity, and thoughts of the energy transition may slip to the back of their minds in favour of the immediate commercial opportunity.

It is wise to take advantage of the upcycle but it would be a mistake to assume this is the latest in the decades-long pattern of oil price undulation. It could be the last true flurry of capital outlay, especially in Europe, and should be treated as a one-off cash injection to fund diversification. Bridging the gap between ultra-high margin oil and gas work and low margin fixed-bottom offshore wind will be critical in achieving a successful transition story.

Calash is an international strategy consultancy that combines seasoned technical and commercial experts and deep sector experience to deliver winning strategies that enable our clients to accelerate value growth. Working across the energy, natural resources, marine, defence and industrial markets, our highly knowledgeable team takes a hands-on approach, delivering concise, tailored outputs and insights that are both pragmatic and commercial.