Investors are beginning to recognise the tangible implications of the energy transition. Instead of a simplistic distinction between clean and dirty investments, there is now a practical emphasis on developing commercially-viable businesses across the energy value chain.

Environmental awareness has been hard-wired into the decision-making process of investment funds – climate risk will remain an investment risk for the foreseeable future – but there has been a sea-change in how this translates to energy transition capital deployment.

The war in Ukraine, energy security, inflation, commodity prices, and the decline in price of technology stocks contributed in 2022 to a reset of energy sector valuations and investment assumptions, with a noticeable softening of views on oil and gas, particularly the latter.

ESG-related investments have lost their shine compared to the criticality – and profitability – of traditional forms of energy. Through the course of the year, ExxonMobil’s share price grew by 79.3%, compared to a 28.6% drop by tech giant Apple.

In the UK, public market appreciation of the energy sector needs to be clear-cut. While success cases have emerged, such as Ashtead Technologies, more established firms like Wood have, until recently, been punished for remaining exposed to oil and gas, while any move to diversify failed to attract any meaningful rerating. Damned if they do, and damned if they don’t.

But the times are changing. Apollo’s repeated attempt to acquire and delist Wood show that the underlying commercial merit of the business has not gone unnoticed by all.

The consequences of this sector reappraisal will continue to be most keenly felt through 2023, as a better-funded and appreciated energy sector gets to work unlocking value through organic investment and M&A.

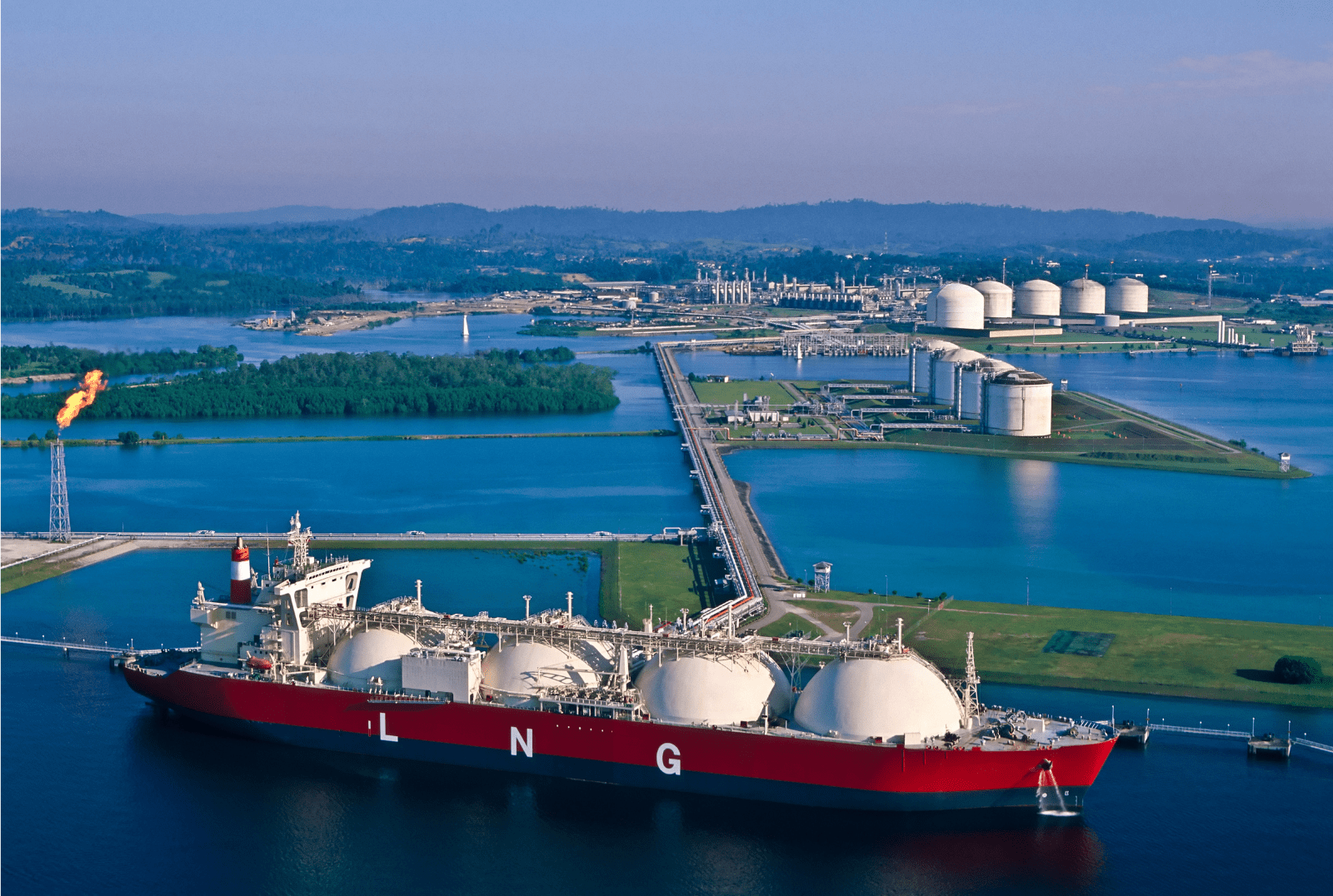

This doesn’t mean there will be a return to private equity and institutional investors targeting businesses with heavy exposure to oil and gas, but it will mean an increasingly holistic view of value creation within the energy supply chain. Practically, meeting the increased demand for service and equipment will become more important than whether the end customer is a gas platform or a floating wind turbine.

And it couldn’t come at a more critical time. The energy transition needs some well-heeled backers.

Capital expenditure in the North Sea is likely to continue increasing over the coming eighteen months. There are serious questions about meeting that demand following a decade of minimal investment in vessels, people, and equipment.

For generalist financial investors, there is now a value creation scenario where the short-term gain from increased oil and gas activity can underpin diversification into emerging markets, such as floating wind. In a nutshell, buying an oil and gas business now for a low sale multiple, taking it credibly into other markets, and then selling it in five years at a much higher premium.

It’s not rocket science, but neither is it easy. The pricing pressure in the renewables sector is notorious ruinous on the profit margin of equipment and service providers. Shifting the revenue base to these markets may increase the EBITDA multiple of the business, but if that EBITDA has shrunk then so will the enterprise value at exit.

Another challenge is people. A significant proportion of the UK’s skilled engineering workforce is nearing retirement without an equal number of newly qualified professionals entering the sector. The renewables sector sucked away many graduates from the oil and gas industry that had been portrayed as in fast decline and morally deficient. Some of that exodus has been arrested in the last year due to the attractive rates created by a strong oil price environment, but there remains an overall deficit in skilled professionals across the board.

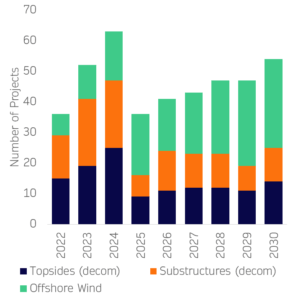

Number of Projects in the North Sea | OEUK, Calash 2023

OEUK predicts that in 2024, several major projects are meant to take place, including 16 offshore windfarms put in place, 22 oil and gas substructures removed, and 25 platform topsides removed, according to research from the trade body. None of these work scope types has ever been done in such volumes in a single year. The complication is compounded when looking at individual works, including considerable platform preparation, heavy lift and post-COP work, all requiring a niche set of skills. Analysis from Calash predicts the increased requirement for people will not subside in 2025 either.

This increase in offshore wind activity poses a potential risk that decommissioning work and other projects could be delayed and targets missed as the supply chain is overwhelmed by a skills shortage. Broadly speaking, the same skills are required to deliver the 50GW of offshore wind planned by 2030, as those needed to deliver billions of pounds of decommissioning work in the UK.

The OEUK is trying to alleviate these issues by drumming up interest in colleges and universities to entice new talent to the sector. The drive for interest is expected to lean increasingly on marketing a role in the energy transition. However, it’s unlikely that any positive benefit from this activity is to be felt for several years.

Understanding these issues, and others like them, underpins a lot of the work that Calash has performed in the last year. Typically, an investment target pitched by its sellers as exposed to renewables or cleantech finds a broad swathe of interested suitors. However, it doesn’t take long for the headline long-term market forecasts to jar with the realities of a flimsy contract pipeline or a business’s internal capability to manage change.

Any closed-end investor must ensure that these challenges can be overcome within a holding period or risk a limited pool of buyers on exit. Funds need confidence that the pace of the broader energy transition will align with business-specific commercial objectives.

Several transactions are ongoing or expected to come to market, which will act as key indicators of how financial investors view the next five years, and the value to be created in a broad approach to the energy transition. It’s an exciting time to be in the energy sector.

By Patrick Harris and James Kirby